SLAC Contributes Cutting-edge Sensor Design to ATLAS Upgrade

A sensor design first envisioned in 1995 by physicists and engineers at SLAC plays a starring role in a major ATLAS detector upgrade at the Large Hadron Collider.

By Lori Ann White

A new type of silicon sensor first developed at SLAC is an important part of an upgrade to the ATLAS pixel detector, the innermost portion of one of the two main instruments at the Large Hadron Collider in Europe.

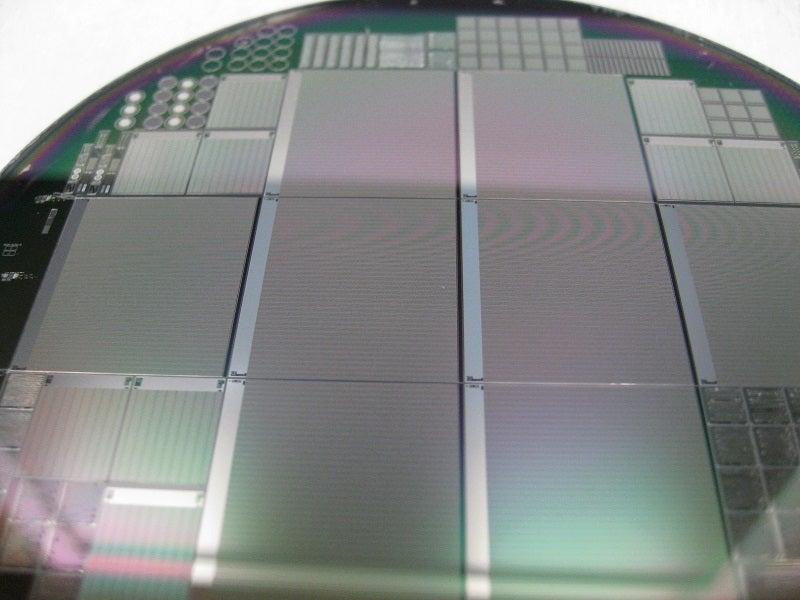

Called 3-D sensors for a unique design that makes better use of the whole chip, the sensors were first proposed in 1995 by Sherwood Parker of the University of Hawaii, who was working on detector technology at SLAC at the time. But it took several years before the first successful prototypes were created at the Stanford Nanofabrication Facility by SLAC engineer Jasmine Hasi and tested at SLAC, and another few years to hand off the design to European chip manufacturers to produce in bulk.

Now, almost two decades later, more than 100 of the sensors are part of the new Insertable B-Layer (IBL) hugging the LHC beam pipe at the core of the ATLAS detector. Inside the beam pipe, just centimeters away, protons smash into protons at close to the speed of light. The collisions produce sprays of particles that are key to understanding all the scientific mysteries being studied at the LHC.

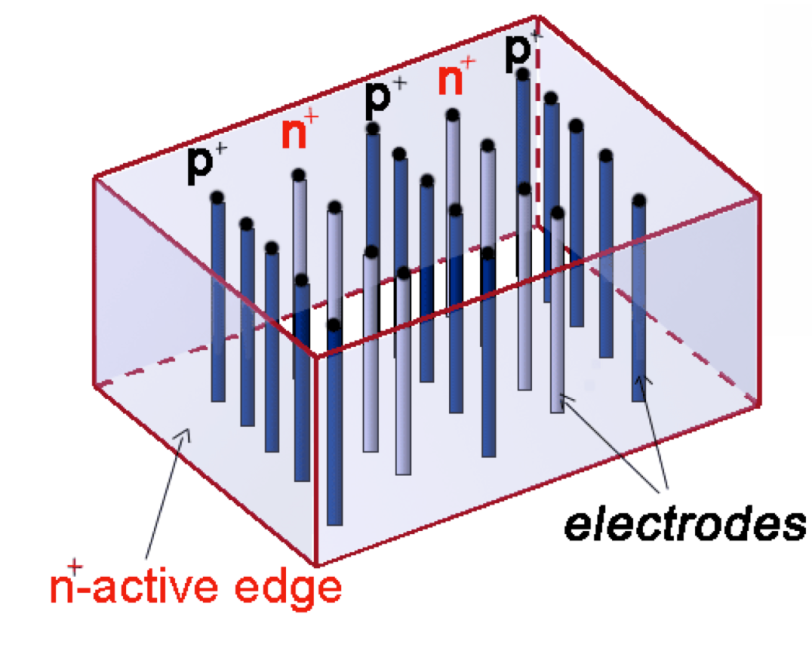

More than 26,000 pixels cover each sensor and map the positions and energies of particles striking them by capturing the resulting electric current. On a standard silicon sensor, the electrodes that capture the current are on the surface. But in the 3-D sensors, the electrodes are embedded in a regular pattern of fine pillars throughout the silicon.

Simple But Radical

Parker's idea of extending the electrodes into the third dimension was "a somewhat simple but radical idea," said SLAC engineer Julie Segal, who has been with the project since Parker first envisioned the new design.

It affords the sensors several advantages, chief of which is their robustness in the face of damage caused by the very particles they're meant to track.

Occasionally a particle passing through a sensor damages the underlying crystal structure of the silicon, interfering with its ability to conduct current. With proton bunches in the beam pipe colliding 40 million times a second, the sheer number of resulting particles can cause enough damage over time to significantly affect the sensors. Such damage cannot be prevented, but the grid of electrodes in a 3-D sensor shortens the distance current must travel before being collected by sensor electronics, improving the odds a signal will miss the affected areas.

Also, since the signals from charged particles don't have as far to travel before they encounter an electrode, these sensors are faster.

The team also made a second design advance that can apply to all silicon sensors: The edges where the sensors butt up against each other are themselves electrodes, called active edges. This makes portions of the chips that were previously dead space into useful material, creating a more complete picture of the particles striking the sensors.

Capturing Important Information

Chris Kenney, a SLAC scientist who specializes in detector design and who is a long-time collaborator of Parker's, put the importance of the new design into perspective.

"The 3-D sensors are the first things to see the particles before their trajectories are altered by multiple scattering and other processes," following a collision, he said. "It's important for the sensors to work well and last a long time because it's important that we get all the information the particles can give us."

Cinzia Da Via of the University of Manchester led the team that took the idea from design to working sensor system for the IBL, with heavy involvement from the SLAC ATLAS group, said SLAC physicist Su Dong, the group's leader.

Parker said he's happy to see the sensors in use in the ATLAS detector, but impatient to develop new applications.

"When you lift the requirements that signals are confined to the top and bottom of a sensor," he said, “you open up lots of possibilities."

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.